The Ride Back: How 5 Minutes Can Shape a Crew

The world has changed, and with it, the fire service. Technology has reshaped the modern fireground in ways we could not have imagined even a decade ago. Thermal imaging, improved data, drone operations, and real-time information sharing now give us faster and more accurate situational awareness than ever before.

One piece of technology more than any other has accelerated the spread of information: the cell phone. It has connected firefighters across the country, sharing training ideas, leadership lessons, and access to people we never would have reached before. But that same acceleration has a cost. The pendulum has swung hard in the other direction. We are more connected than ever, yet increasingly absent from the people sitting next to us—sometimes even in the cab on the way to the call.

Social media is often labeled a distraction, and at times it is. But it does not infect one generation more than another, as is so often claimed. If anything, the younger generation is simply more comfortable navigating it. What concerns me more is what happens during the quiet moments of the job.

Those stretches of time that once belonged to conversation, storytelling, debate, and mentorship. In the cab on the way back from a call. In the station between runs. Around the kitchen table. What once held shared experience now too often feels like isolation. We retreat into our own digital worlds, chasing the small dopamine hits we have all grown accustomed to.

But within that shift, I see an opportunity.

Leadership is often imagined on a big stage, in front of large crowds, attached to big and important topics. That version of leadership is visible, but it is not where culture is built. Real leadership does not crash into an organization. It seeps into it through small, ordinary moments.

It looks for chances to shape tone, steady direction, and point people back toward the mission.

Because here, in the middle of the organization, the most important work is done. This is where operational culture is driven. This is where influence actually exists. This is where vision is built.

Officers and senior firefighters should recognize these moments and take advantage of them. A simple question after a call can open the door to learning. What worked? What didn’t? What would we do differently next time, if anything? These conversations do not need to be formal or lengthy. They create space for younger firefighters to ask questions, think critically, and better understand both the craft and the responsibility of service. This is how culture is passed down.

The same way it was handed to us. Not through policy. Not through memos. But through conversation, mentorship, and the decision to stay present instead of drifting into distraction.

If we are looking for a way to bring some of that culture back, we do not need to invent anything new. We just need to reclaim the moments we already have. One of the most overlooked and accessible training opportunities sits right in front of us on every call: the ride back to the station.

It requires no scheduling, no planning, and no buy-in beyond intention. Everyone is already there. No one can leave. There are no competing meetings, no emails to answer, no side projects pulling attention away. It is one of the few guaranteed windows in the shift where a crew is together and focused on the same experience. We should not let that time disappear into silence or distraction. Put the phones away. Do not miss the lesson rolling past you.

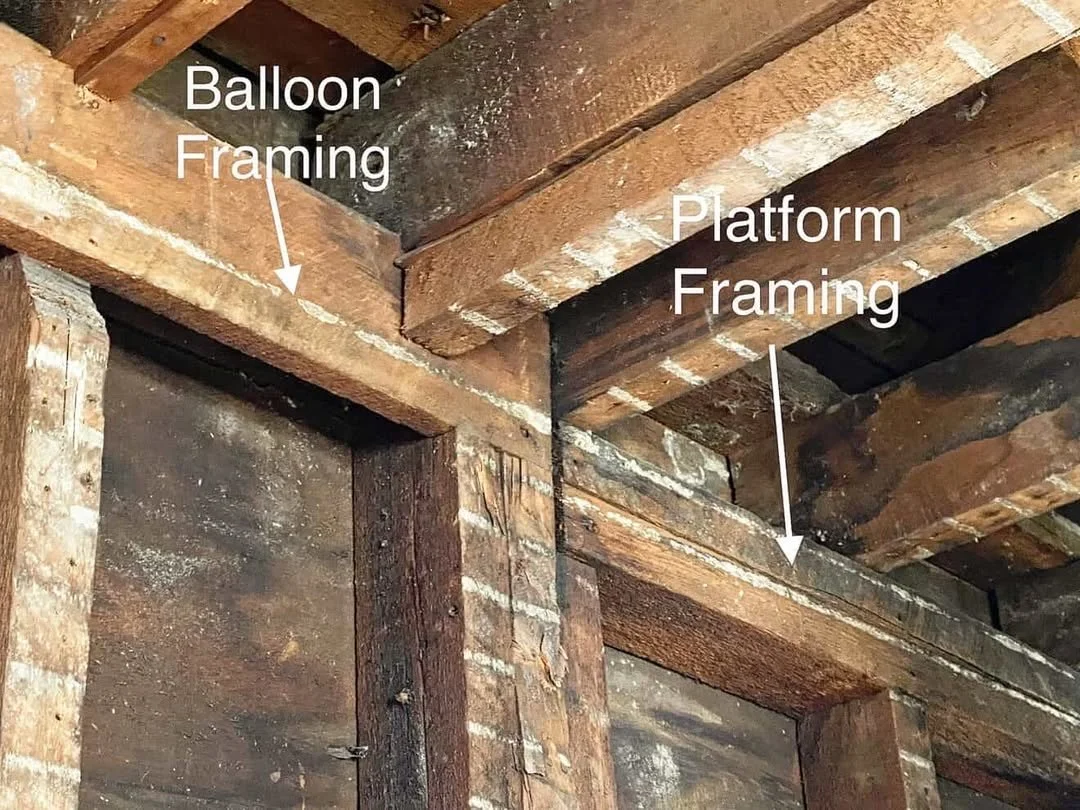

One of the most powerful uses of that time is district familiarization. Every block you pass offers an opportunity for discussion. A company officer can point to a structure and engage the crew.

What type of building is that? What are the access challenges? Where would you spot the first-due engine or truck? What does your hose stretch look like from that corner? If this were aworking fire, where do you expect fire travel, and where do you want crews operating?

Construction type. Setbacks. Access. Water supply. Sometimes the best outcome is simply recognizing a building worth stopping at later for a closer look.

The ride back also provides a low-pressure opportunity to build driver and district proficiency.

Take a different route home, not randomly, but deliberately. Explore tight streets, alternate approaches, and areas that are rarely used on routine responses. Ask the backseat to call out hydrants, dead ends, or overhead obstructions. Ask the driver why they chose one route over another. Turn it into a problem-solving exercise rather than a test. What changes if we are second due? What changes if the truck is coming from a different direction? What changes at night?

These small repetitions build spatial awareness that only comes from moving through the district with intention. We need to get our heads out of our cellphones.

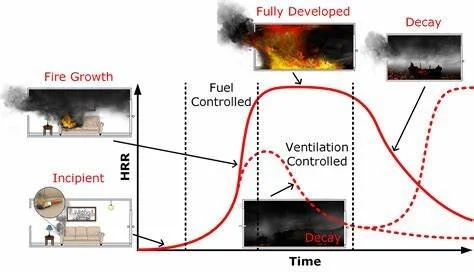

Finally, the ride back is an opportunity for immediate after-action discussion. Not a critique. Not a formal breakdown. Just a simple crew reflection while the call is still fresh. What went well?

What surprised you? What would you do differently next time? These short conversations normalize learning and reinforce that improvement is part of the job. It is important that these discussions are not only reactions to failure. They should also acknowledge what went right.

They give newer firefighters permission to think out loud and process decisions before habits harden.

None of this takes long. Five minutes is enough. Ten minutes is a gift. The value is not in how much you cover, but in how often you choose to engage. When crews expect the ride back to include conversation, awareness follows. Learning follows. Culture follows. When we miss that window, we miss more than time. We miss a chance to turn routine responses into deliberate development. That choice presents itself on every call. The question is whether we are intentional enough to take it.

Authored by:

Mike Elhini - Front Seat Academy

Marc Symkowick - The Holdfast Project