BLEVE Hazards and Mitigation: Understanding Boiling Liquid Expanding Vapor Explosions Part 2 – The Mitigation

This is the second part of our blog series about BLEVEs, where we will discuss ways firefighters can mitigate the associated hazards.

Strategies for Firefighters

Preventing BLEVE incidents and minimizing their impact requires a comprehensive approach. The first step is through risk assessment and pre-incident planning. Get out in your first due and identify locations with BLEVE potential (garages, storage yards, industrial facilities). You should conduct pre-incident surveys and coordinate with owners and facility operators about vessel types and containment systems. If operating at a commercial/industrial facility, ensure emergency plans are available and up to date. If it is a residential or light commercial facility where the tank may be rented from a fuel supplier, consider requiring a way for the name of the company and contact information to be obtained without having to approach the container. There is a good chance the name will be on the tank for advertising purposes. However, the name may not be there, has degraded over time due to the elements, or it is not visible due to active fire. The tank company could be a resource for information regarding operations or overhaul.

Maintain disciplined scene management and determine a safe approach route. Establish your hot zone based on vessel size. The Emergency Response Guidebook (ERG) has a section towards the back regarding BLEVE safety and provides suggested fireball size, evacuation distance, and cooling water flow. Consider having this zone predetermined on a case-by-case basis and available in pre-plan information. Strict access control must be employed, and civilians and non-essential personnel need to be evacuated beyond the projected hazard radius. Approach to a vessel should be made from an upwind and uphill position to reduce exposure to vapor and projectiles. It has also been suggested that an approach should not be made straight onto the end caps for safety in the event of a tank deflagration. Firefighters should attempt to make use of any available cover, such as barriers, apparatus, or terrain, when operating near vessels at risk.

A large quantity of water will be required to cool exposed vessel surfaces. The application of water should be focused on the vapor space above the liquid, where the metal is most vulnerable. Avoid directing water directly at a leak as this may cause freezing of the water. Firefighters should continually monitor the vessel temperature with thermal imaging cameras to assess cooling effectiveness and identify an increase in temperature. Do not attempt to extinguish the fire at the base of the vessel until cooling is assured and venting from relief valves has stabilized. If cooling is not effective or container deformation is observed, withdraw to a safe distance immediately.

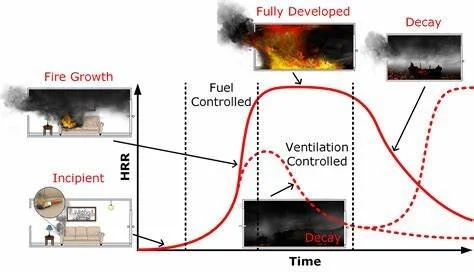

Pressure relief valves are the first line of defense against a BLEVE. Having a relief valve “blow off” excess pressure is not a bad sign. They are safety devices designed to automatically release excess pressure from a vessel to prevent pressure from rising to dangerous levels. They are set to open at a predetermined pressure and then close once normal conditions are restored. They will cycle between being open and closed if the tank cannot be sufficiently cooled. However, while the PRV vents pressure, it does not prevent the BLEVE itself. This cycling of venting is an indication that more liquid is being converted to a gaseous state. The venting reduces the liquid level, which exposes more of the vessel's metal to heat, potentially weakening it and increasing the likelihood of a BLEVE.

Avoid direct intervention on vessels showing signs of imminent failure.

Firefighters should wear full turnout gear and SCBA when operating near vessels at risk of BLEVE. Apparatus should be positioned outside of the hazard zone to prevent loss of or damage to vehicles and equipment.

Conclusion

BLEVEs are among the most dangerous situations firefighters may encounter. These events combine explosive force, intense heat, and unpredictable projectiles. To mitigate these hazards, firefighters must prioritize knowledge, preparation, and strict adherence to safety protocols. By conducting risk assessments, undergoing proper training, using protective equipment, and taking decisive action, firefighters can significantly reduce risks to themselves and the public. Maintaining vigilance and respecting the tremendous power of pressurized vessels is essential for a firefighter's defense against the threat of a BLEVE.